By Becky Furuta:

The romance of pedaling the open road is well established: the camaraderie between strangers, the innate introspection, the breaking-down and getting lost and being found again.

The lure of escape and the search for transcendence were the auspices under which I began riding my bicycle. I was fifteen the first time I slipped out from underneath a rough blanket in a cheap roadside motel along highway 50 near Montrose and hopped on an old Diamondback mountain bike. I paused at the door, wondering if I should bring something along to eat. It would mean stepping over my two little sisters, sharing a rotting mattress on the floor beside the toilet and the mop bucket, near where the mice lived. I decided instead to ignore the emptiness welling up inside my gut and took a long drink of warm water to calm the gnawing.

It was early fall on Colorado’s western slope and the mornings were bitterly cold, but so was the motel. My mother had resorted to heating the baby’s crib with a hair dryer carefully perched on a stack of phone books. The six of us – my sisters and I – would huddle tightly on the dirty, cracked linoleum floor when it was time to eat, so that it sometimes felt like in our effort to stay warm we were stealing all the oxygen from one another. It was too many bodies too close together to breath. In fact, everything about the motel felt that way.

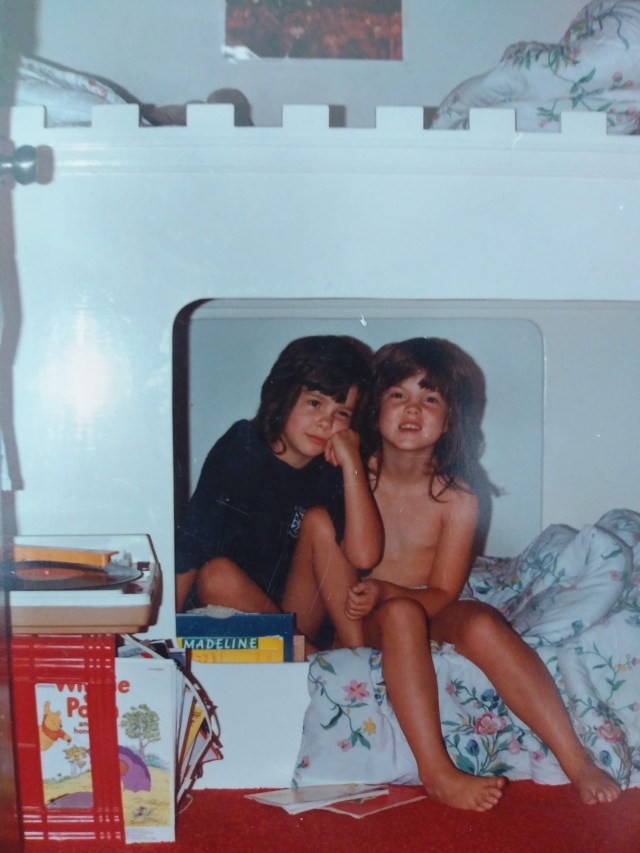

It wasn’t always like that. Once, I had a home and went to school. I had friends and played sports. Things were still hard – my father was erratic and unpredictable. Any transgression might bring about a beating. My mother had uncontrolled type two diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and was constantly ill. She spent her days smoking cigarettes at the kitchen table, waiting to die. Our school clothes were stained, my little sister’s hair was a hopeless mess of tangles, and the food in the pantry was rotting. All it took was a series of medical calamities and my father’s impulsiveness to plunge us into homelessness.

So, I found myself at the Will Roger’s Motel with my three sisters and my mother and father, and that beat up old mountain bike. It took me only days to plan my escape. I would get up early, creep outside before anyone could stop me, and ride until the sun went down. I had no direction. To be honest, I didn’t even know where I was. I would wake up 1000 mornings in a row, point my bicycle toward any road that pulled me, and I would fly.

The road left me time for rumination and quiet moments inside my head. My life was filled with so much noise – screaming and crying and breaking glass and sirens. As a little kid, I would lay in bed at night and listen to my father tormenting my mother, putting his fists through walls and making her wail. I would lay there in total stillness, terrified to even breath too loudly. I would wet the bed because I was afraid of what he would do to me if he saw me awake. The bike created a space in my life where honesty was welcomed and the full layers of my complexities were honored. There was no walking on eggshells. No holding my breath. The noise stopped.

I climbed steep mountain roads and dropped down into canyons alongside rivers and lakes. I marveled at the kindnesses of strangers, learned to fix flats and wrap spokes, got bored and felt my entire body ache after long days in the saddle. It was absolute magic.

The western slope is filled with sublime natural beauty. On the way out of town, I would watch the sun rise over soybean and corn fields, cresting on the Grand Mesa and over orchards with every sort of stone fruit. I stared down from the thin strip of tarmac along the Million Dollar Highway at the canyons down below, and wondered what would happen if I flung my body over the edge. I glimpsed red rock walls and was dwarfed in the shade of peaks.

In the confines of the tiny motel, everything was exposed – marital spats, frayed underwear, the onset of puberty, the unchecked tempers and the mischief of rambunctious kids. On my bicycle, I felt hidden away to the world. I was small amid the expanse. I would tell myself, “I’m going to ride until the next bend in the road,” only to get there and find myself pulled to see what was up ahead.

And I got fast. So fast, people started to notice. When I finally went to school a year later, I joined the mountain bike team. It was immediately clear that I was faster than any of the boys.

Abuse, poverty and homelessness are tough enough. Harder still was living with the stigma that accompany them. No one expects much from you when your address is a motel, when your clothes are dirty, when you haven’t showered because there’s no running water. My teachers were fluxsummoned. After missing more than half of my classes one year, I was summoned to the principal’s office during lunch period. I remember examining the food on my tray, trying not to cry as she lit into me, hungry but too proud to eat. “Can you hurry up and eat that,” she questioned. “The drama with the pizza isn’t working for me.” I sat, perfectly still. Said nothing. “You are a waste of time,” she added.

Cycling changed all that. Suddenly, I was racing and winning. I was strong and capable, and people saw me. They wouldn’t invest in the homeless kid, but they invested in the talented athlete. The bike kept me in school so I could keep racing and doing what I loved. Eventually, I would attend university on cycling scholarships, earn a degree in public health, and fashion a long career in pro cycling. I went from being the problem child, the lost cause, the “waste of time” to being the long shot, the Hail Mary, the overcomer.

At fifteen, I papered the walls in my corner of the motel with clippings from travel magazines – far off places I dreamed of being. As an adult, racing with some of the top teams in the sport, I saw those places from the seat of my bicycle. I have more than two decades in elite and professional cycling behind me, and I am as in love with my bike today as I was back then.

Still, after all these years and all the places I have seen, my favorite roads are the ones that became my home. In a world where I could never find my place with people who never seemed to understand me, the bike became home. It was where I felt safe and happy and at peace with myself. To be honest, I don’t remember too much of my childhood. Disassociation and PTSD robbed me of my memories, for better or worse. But I still remember the turning of pedals and looking out at the San Juan’s and Blue Mesa Reservoir.

The vague spirituality of cycling has guided many tours, and the 35th annual Ride the Rockies is no exception. The event takes riders on Colorado’s most scenic roads, with breathtaking views and long, hard climbs. This year, the routes wind their way through the mountains of my youth, trickle alongside the banks of the Las Animas River, through Ute tribal lands and up the Uncompahgre Plateau.

These are the roads that brought me home. They are where I became strong like the boys and fast like wind.

It’s odd to think of thousands of bicycles blanketing the solitary spaces I rode as a teen, but I am happy to share them. There are no better views than the San Juan Skyway, Wilson Peak rising to the sun, the Lizard Head Wilderness surrounding you as you ascend.

Yes, Ride the Rockies demands more stamina than the standard single-day century, but in exchange you are rewarded by snow-capped peaks and open valleys. Let every hard moment be a celebration of your efforts and your endurance, and fall in love with every turn. Those are the lessons I learned on the roads participants will ride. When your heart is beating and the wind is brushing the tiny hairs on your face and the beautiful scenery is stealing your breath, I hope you’ll find your own transcendent moments.